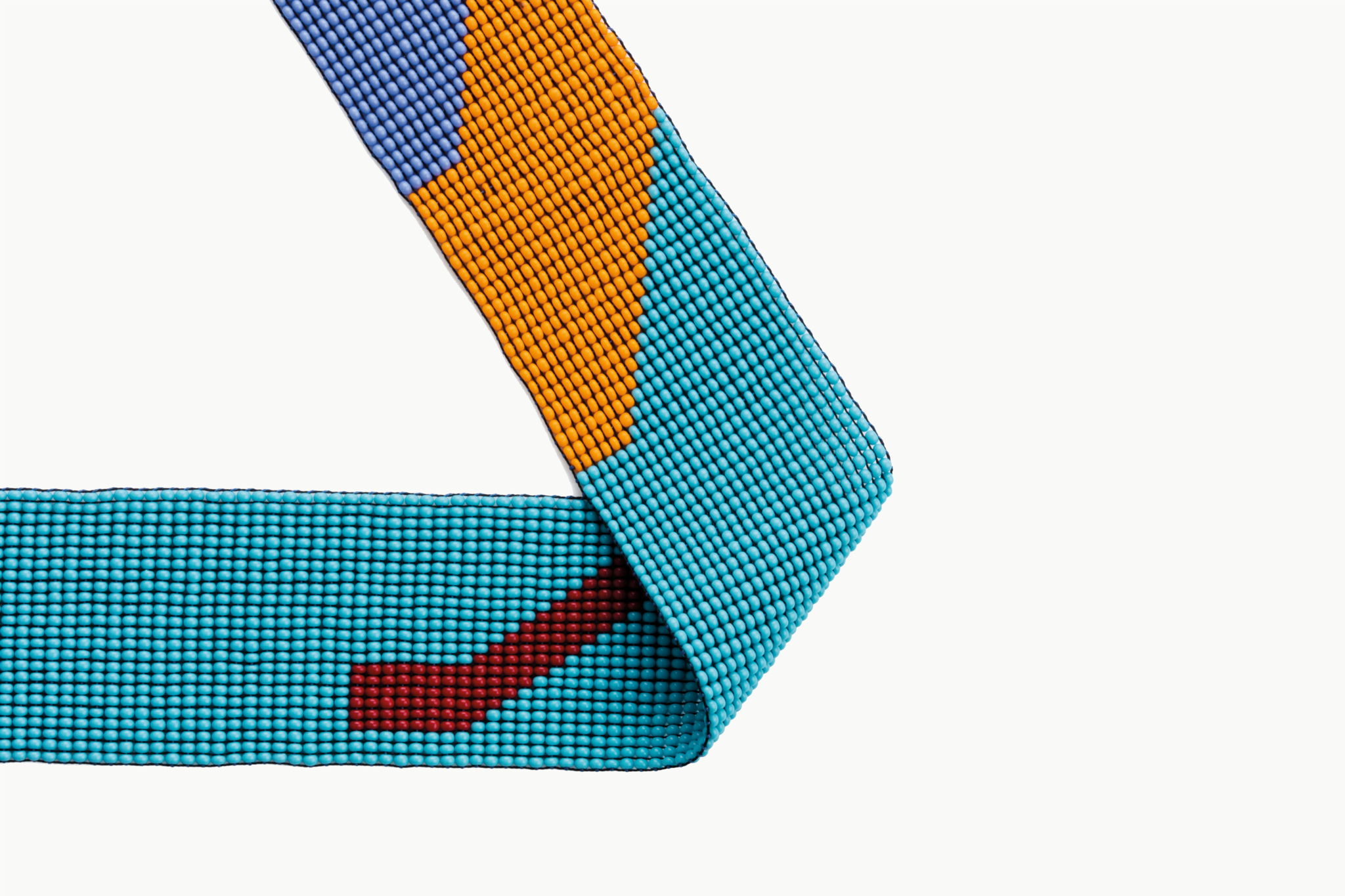

Last year I was introduced to the Zimbabwe-based Marigold Beads. The project was established in the early 1990s to provide livelihoods for women in Zimbabwe’s second largest city of Bulawayo who, for various reasons, left formal education at an early age. Today the center operates as a co-operative with Johannesburg-based artist Joni Brenner contributing to a collaborative model of design development with the bead weavers. As necklaces their palettes and patterns are utterly contemporary, while drawing on a rich heritage of bead work historically found across southern Africa. More recently the bead weavers have also embarked on unconventional collaborations such as converting the data of genome research into poetic color fields.

“I’m often asked, who is the designer?” Brenner explains of her partnership with the bead looming co-operative Marigold. The artist’s contribution to Marigold, which is located nearly 900 kilometers north in Bulawayo, now extends over thirteen years. “Because the beaders are far away,” Brenner reflects when we recently spoke, “I rely on them to take control of the monthly production. It is important there is a shared understanding, a learning process and constant negotiation of the designs.”

Established in the early 1990s, the original Marigold members attended workshops aimed at the development of self-sustaining co-operatives led by the Danish aid organization Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke. But by the mid-2000s Zimbabwe’s economy was in freefall and this, coupled with a decline in tourism, threatened the co-operative’s survival. The tenacity of three founding members – Siphiwe Dube, Sifiso Mathe and Teresa Nkomo – kept Marigold alive.

From left: Concilia Mukarobwa, Dzidzai Shemaiah Hwende, founding member Siphiwe Dube, Similo Moyo, Thokozile Maseko.

Clockwise from top: Ridia John Samson, Thokozile Maseko, baby Michael Junior Mtore, Concilia Mukarobwa, Similo Moyo, Simangele Dube, Jambo Sibanda.

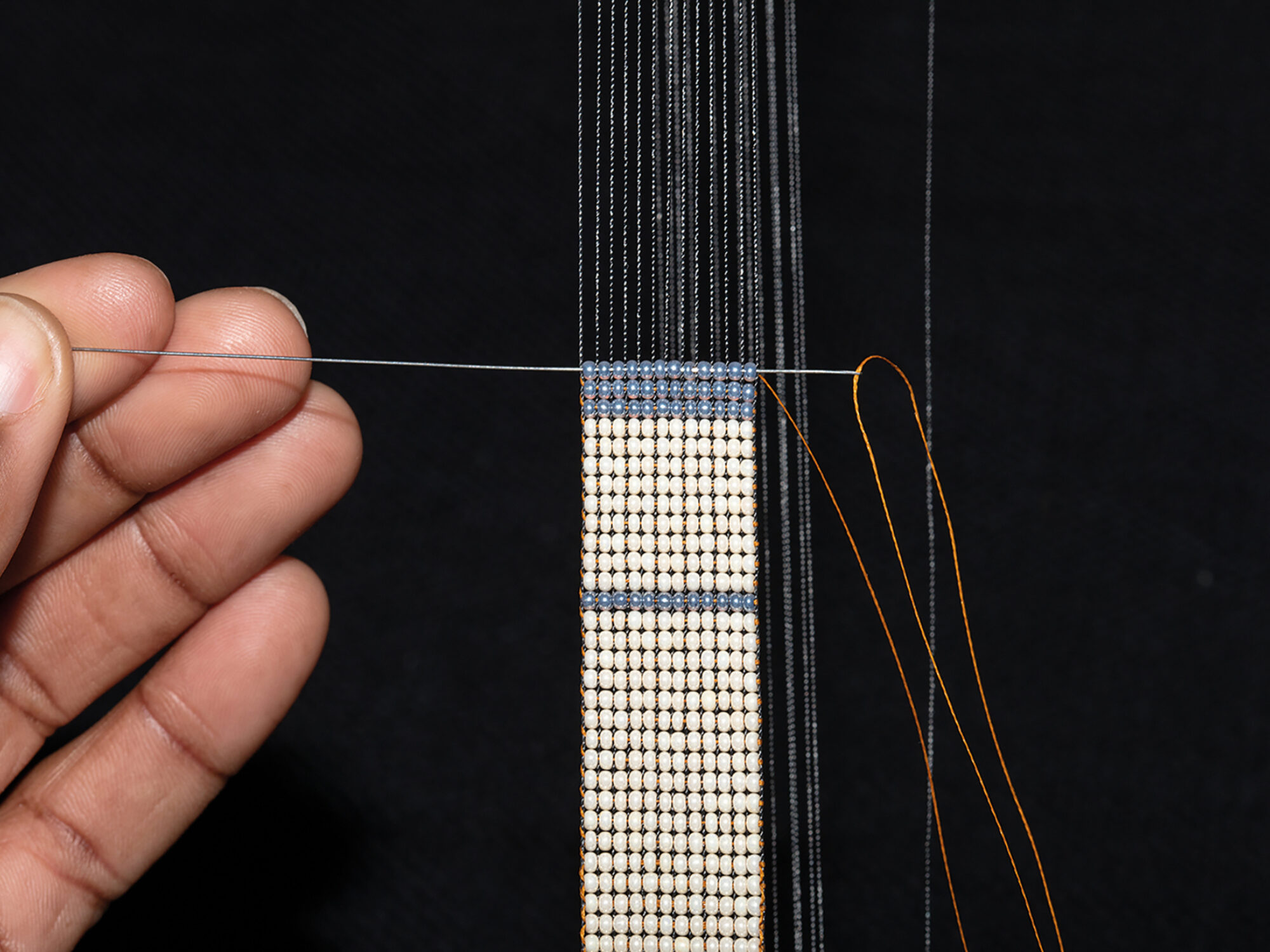

Frame-based Beadweaving

While beadwork appears across the continent of Africa, the introduction of bead-loomed production to Bulawayo remains a mystery. The oral history of the co-operative remembers that Danish support originally provided materials, but the knowledge of bead weaving on a frame is attributed to “Margaret’s mother”. In the publication Making Marigold: Beaders of Bulawayo (Palimpsest: 2017), Brenner and Elizabeth Burroughs write:

The beaders are clear that both Margaret and her mother were Bulawayo people and lived in Pelandaba. Siphiwe Dube also recalls that Margaret’s mother had produced loomed mohair sweaters and scarves. No one at Marigold knows how Margaret’s mother had learned to loom beads or where, but it was she, not the Danes, who taught them the craft. Strange as it may seem, no one remembers Margaret’s surname, or her mother’s (p. 57).

Teresa Nkomo one of the founding members of Marigold.

Crediting individual makers by name has been used globally as a strategy to overcome the anonymity of craft production. But it isn’t an approach that accurately reflects the nature of much craft production. In Marigold’s studio, four or five beaders work around each table. Other than some specialist tasks such as stitch-joining the strands into a loop, the work is understood and identified by the women as the co-operative’s. “When I ask who made a specific necklace, it is not always known. The classic narrow necklaces are made in groups of three – they are almost the same, bar slight differences in length and perhaps one or two other shifts, where perhaps one is in a different green bead to the other two. Longer necklaces can often be the work of two people.” Brenner’s question of attribution remains unanswered.

Today Marigold’s one hundred and thirty variations and counting of handloomed necklaces are based on a consistent format of a single loop in lengths of fifty-six to sixty centimeters long, with between 4800 to 5000 beads in each necklace. Wider, longer and thinner variations are also produced with the longest, once joined, about one hundred and twenty centimeters, which allows for wrapping two and even three times around the neck. Depending on the complexity of the design and the amount of color combinations required for a necklace, production can take anything from one day to one week or more.

the Unexpected

Many of the successful Marigold designs are reused, often with slight variations introduced by the team. Brenner recently sent the weavers a picture of a Joseph Albers’ drawing asking for their input in its potential as inspiration for a new design. “We have worked together for so long they know when I send a drawing that it is a suggestion,” she explains. Sometimes a design that is entirely new to the beaders is plotted on graph paper and, in discussion, designs are then adjusted. Time is often necessary to allow the unexpected to emerge. Color ranges evolve with time. “If we are not sure about a design, it is tried in several different color-ways to ascertain whether the idea is worth continuing,” Brenner explains of the role patience plays in seeing through a creative idea.

Each month necklaces arrive in Johannesburg, tangled together from the jostle of their overland journey. Brenner checks each for quality and sends photos with comments back to the beaders. A cascading communication structure was set up by the co-operative’s three leaders to allow Brenner’s thoughts about the designs to be shared with the team in their own languages, allowing solutions to emerge from amongst the beaders themselves. “When I’m not sure about a necklace I have to be able to explain why,” Brenner explains. “It is helpful that I have my own practice as a visual artist and I know that experimentation, risk and trying things to see what emerges are important parts of any creative practice.”

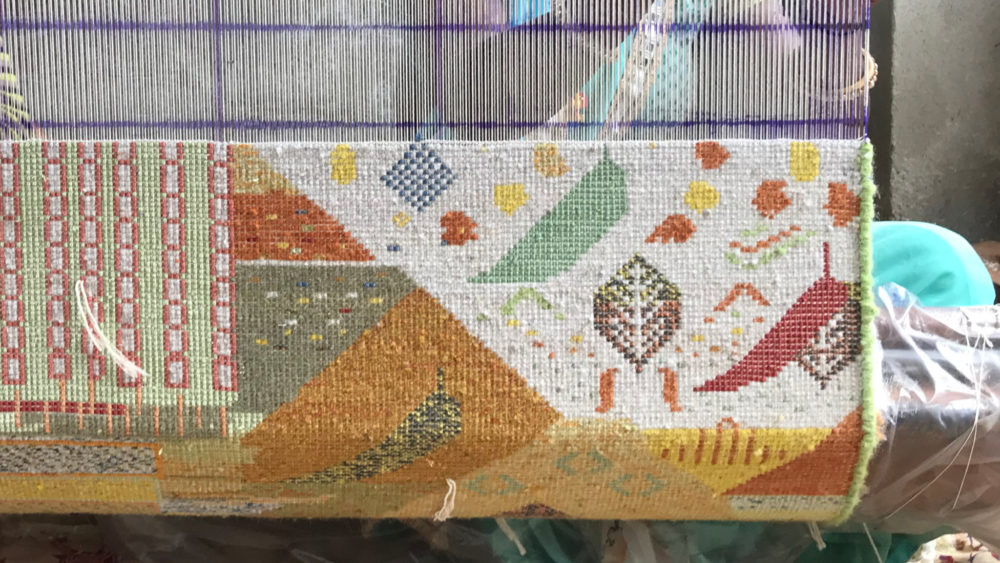

Genome Beadwork 2024.

Genome Beadwork 2024.

Genome Beadwork 2024.

Ironically, Marigold’s commitment in 2011 to a single type of product may explain the co-operative’s longevity. Working exclusively with the form of the looped necklace means the technique has been perfected, allowing for room to focus on risk taking in the design and color combinations. Working with one simple form allows the beaders to focus on the question: “what small change can we make to this specific necklace pattern to create something different?” Close attention is given to how a particular range of designs coheres with the necklaces sent to Brenner monthly often suggesting a collection or set.

The ongoing process of making small changes to existing designs continues today, including designs that have taken Marigold in novel directions. On occasion the team undertake special projects with the necklace form tasked to carry unusual sources of inspiration. Brenner, for example, saw the visual data maps her husband, Scott Hazelhurst, was producing with the team of scientists working at the Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience at the University of the Witwatersrand, and realized there could be a new application for Marigold’s skills. The team’s data maps the genetic admixture of various population groups that aid understanding of population interactions on the African continent over the past 5000 years. Marigold has produced beaded interpretations of the data in 2017 and, using updated scientific data, again in 2024. The latter marked the tenth anniversary of the Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience (SBIMB) at the University of the Witwatersrand where the team’s significant research is ongoing.

Right: Teresa Nkomo, Sifiso Mathe and Siphiwe Dube

in One Idea

Sustaining duration is often a challenge for craft co-operatives. A large part of Marigold’s longevity can be attributed to the tenacity of the beaders themselves. But Brenner’s outlook is also crucial. The fact that she is a practicing artist in her own right explains a lot. Her own work often explores portraits of the same person created over years, moving between materials but committed to a single subject. Brenner’s artistic work, not unlike Marigold’s, involves a commitment to the creative insights prompted by repetition. “We work in an organic way, paying attention to each new design as it emerges,” she offers. “Thinking about where it might go next keeps a product alive.”

Acknowledging the significance of her role in the Marigold co-operative, her aesthetic and eye, and her capacity to position the work of the project, Brenner returns to a crucial point: “I understand what it takes to be an artist. It is necessary to not have pressure, to engage in feedback and discussion, and to remain curious and open to possibilities.” Ultimately, her sensitive and collaborative involvement in the development and continuity of Marigold allows the production of the co-operative to represent her creative voice enmeshed with the creative voices of the sixteen beaders in Bulawayo.

Marigold's current group members are Siphiwe Dube, Sifiso Mathe, Teresa Nkomo (three founder members), Nothando Bhebhe, Simangele Dube, Dzidzai Shemaiah Mushipe, Nobuhle Jiyani, Thokozile Maseko, Similo Moyo, Egnes Mturiki, Concilia Mukarobwa, Lethukuthula Ncube, Nokuthula Ndlovu, Sikhangele Nkomo, Jestinah Nyoni, Ridia John Samson.

Joni Brenner is a Johannesburg based visual artist and collaborator with the Marigold beadwork co-operative in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. She is a lecturer in Interdisciplinary Arts and Culture Studies at the Wits School of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. She has a Master’s degree in Fine Arts (Wits 1996). Her current research interests are in the scholarship of teaching and learning, and in the relationship between art and science related disciplines.

Jessica Hemmings writes about textiles. Some of these words form academic research; others are read as journalism. Translations of writing have been published in French, Hungarian, Icelandic, Norwegian, Portuguese, Russian and Swedish. She is Professor of Craft and Editor-in-Chief of PARSE at HDK-Valand, University of Gothenburg, Professor II

at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design, Visiting Professor at Moholy-Nagy University of Art & Design, Budapest and was the Rita Bolland Fellow at the Research Centre for Material Culture, the Netherlands (2020-2023). Current research is funded by The Swedish Research Council (2025-2027) under the title “Carceral Craft: the material of oppression or expression?”.

EDITING: COPYRIGHT © MOOWON MAGAZINE /MONA KIM PROJECTS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TEXT: COPYRIGHT © JESSICA HEMMINGS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PHOTOS: COPYRIGHT © LIZ WHITTER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO ACQUIRE USAGE RIGHTS, PLEASE CONTACT US at HELLO@MOOWON.COM